How and when to find a common ancestor

I finally did it!

Did what?

I figured out my relationship to Henry Clay, the 19th century American statesman.

How?

By finding our common ancestor.

Once upon a time, my Grandma Clay told me we were related to Henry Clay, about whom I had learned in school. (That’s what we called my paternal great-grandmother Bettie Islery Pearson Clay, who lived 1880-1977.) She even told me HOW we were related. But I was 12 years old at the time. Did I write it down? No-o-o-o! Sadly, she died long before I became interested in genealogy.

Later, when I started researching my family history, I couldn’t remember what she said. Was Henry Clay her late husband’s great-uncle? Or something like that? Well, no, not that I could demonstrate. Maybe she was just guessing how we were related? I wondered for years if it was even true. My Clays were from North Carolina (as far back as I had researched them, that is). And Henry Clay represented Kentucky in both the U.S. Senate and House of Representatives, having been born and raised in Virginia. But those are all neighboring states. Surely all Clays from that region were related, however distantly?

We’re all related

Over time, my idea of “relatedness” has expanded greatly. I am now fairly obsessed with the idea that we are all related. When people with the same super-unusual surname claim “no relation” I think: Well, maybe you’ve never met, but I’ll bet you have a common ancestor!

Each year at the FamilySearch-sponsored RootsTech conference I look forward to seeing how I’m related to other attendees using the Relatives at RootsTech app. The basis for these calculations is a gigantic crowd-sourced world tree. If you and another attendee have enough generations on the tree to connect with each other via a common ancestor, Relatives at RootsTech will show you how you’re related. Your common ancestor could be 15 generations back, but still, you’re related. (Sadly, Relatives at RootsTech is not available all year long.)

These purported relationships are, of course, completely dependent on the accuracy of the intersecting tree branches. So, if accuracy is important to you, you must treat each new branch and leaf as a clue, not a fact, verifying and documenting each one along the respective paths to your common ancestor. (If accuracy is not important to you, please do the genealogy world a favor and stay away from FamilySearch and make your Ancestry tree “private” so no one gets mislead and perpetuates your errors!)

Here’s another blog post I wrote about how related we all are: Are we all descended from royalty?

How I found our common ancestor

So, I created a private quick and dirty tree for Henry Clay, and I extended my own Clay line by a few generations as well. It was quick and dirty in that it included more educated guesses and less documentation than usual. I made it private in the settings (as opposed to public) so that if it contains errors, no one will find it and be tempted to copy it, thus perpetuating the errors.

When I got to the point where I realized Charles Clay (1638–1686 Virginia) appeared on both trees, I stopped. I had just learned that I am descended from Charles’ son Thomas, whereas Henry Clay is descended from Charles’ son Henry. I then added Charles and his descendants (just his son, grandson, great-grandson, and 2X great-grandson Henry) to MY tree (just their names plus birth and death dates; not all their siblings, wives, children, and the usual documentation for all the above). I did this for the sole purpose of letting the Ancestry computer calculate our relationship.

How am I related to Henry Clay, then?

He’s my 3rd cousin 5X removed.

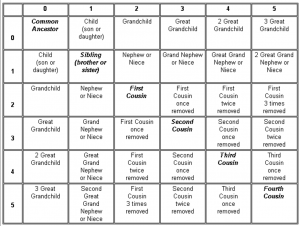

For perspective, he’s probably got thousands of 3rd cousins 5X removed! When determining cousin relationships, as described in this blog post — What the heck is a second cousin once removed? —it’s important to know who the common ancestor is.

When to look for a common ancestor

Cousin relationships are not the only reason to look for common ancestors.

Outside of an app that finds the connection for you, if two trees — belonging to two DNA matches, for example — do not already contain a common ancestor, it’s still possible to find the link with a little (or a lot) of work. Essentially, one must do enough research to extend both trees back far enough to encounter a common ancestor. I do this when I suspect there’s something to gain from it. Like being able to link up with a DNA match’s well-researched tree that promises to provide clues for my own tree. Or, a couple of times I’ve suspected I was related to a client I was doing research for and was able to prove it!

If you have watched genealogist CeCe Moore in her show, The Genetic Detective, you have seen her do this — find a common ancestor between a piece of DNA evidence and a DNA genealogy match. Then, using reverse genealogy — tracing descendants, rather than ascendants — she narrows down the field of suspect candidate(s) for the crime she is trying to solve. If factors such as timeframe, location, and the expected degree of DNA match (number of centimorgans) all come together, a DNA sample is taken from the suspect (if possible) to confirm.

This same technique is used when searching for birth parents and long lost relatives.

So what?

Good question!

I wasn’t even sure I wanted to be related to Henry Clay. All I could remember about him was that he ran for President five times and lost, saying, at some point, “I’d rather be right than president!” But, honestly, I didn’t even know what he thought he was right about. Was he just a big loser suffering from sour grapes? Or did he contribute greatly to his country? Or both? I’d also heard him called The Great Compromiser. Was that meant as a compliment? Or as an insult? How does compromising make sense if he always thought he was right? What sorts of compromises did he make?

So I did some research.

There are roughly a gazillion Google results for Henry Clay. Add “statesman” to the search and you still get well over a million hits. Depending on who wrote the article, book, or website, and depending on their audience — general public, children, historians, etc. — you will find various perspectives on his life and times.

Turns out he only ran for president three times, and unsuccessfully sought his party’s nomination two other times. Whatever. But guess who voted for him — twice — and eulogized him at length upon his death? Abraham Lincoln!

Clay and slavery

Oh. So that’s what he thought he was right about.

He seems to have been a greatly admired and very complicated man. He was outspoken in opposition to slavery, while simultaneously owning and buying slaves. A lot of them. This, naturally, drew criticism from all sides. His Compromise of 1850 (which contains a boatload of provisions) is generally credited with delaying civil war long enough that the Union could prevail and emerge intact. But the northern Quakers considered him a hypocrite, while the southern slaveholders considered him an abolitionist. (He believed in the gradual emancipation and eventual return of freed slaves to Africa.) Thus he never did get quite enough votes to win the Presidency. (Although he did come within 5000 votes once.)

Meanwhile, he served his country for decades, and he was regarded so highly that when he died in 1852 he was given the honor of the first person to lie in state in the Capitol Rotunda. (It was finished in 1824, so there were 28 years in which someone else could have been the first and wasn’t.) They also took his body on tour! Note on this map that the tour was only of the northern states, not the southern states, an indication of where he was more popular.

Yes, he was highly regarded — by white men, that is. Who knows what the not-yet-allowed-to-vote women thought? And the free people of color? As for the enslaved, I would imagine their opinions varied according to whether they lived at Ashland (Clay’s plantation), or elsewhere, and what they heard about him (if anything) from others.

What is a statesman, exactly?

I got curious about why Henry Clay is usually referred to as a “statesman” and not a “politician”. I googled it and came up with this quote (among many similar sentiments):

The difference between a politician and a statesman is that a politician thinks about the next election, while the statesman thinks about the next generation. ― James Freeman Clarke

I was prompted to take another look at Henry Clay while reading Chesapeake, by James Michener. (A novel that covers a few hundred years of history in that area.) Michener wrote, from the perspective of one of his characters:

How sardonic it was, Paul thought, that the three greatest men he had known — Clay, Webster, Calhoun — had each sought the presidency and been rebuffed. Always we elected men of lesser quality. He counted off the grim procession of incompetence who had occupied the White House during these years of crisis: Van Buren, with no character; General Harrison with no ability; John Tyler, God forbid; Polk, who allowed everything to slip away; General Taylor, lacking any capacity for leadership; the unspeakable Millard Filmore; Franklin Pierce, who was laughable; James Buchanan, who could have averted this war; and now Abraham Lincoln, traitor to all the principles he once professed. He recalled fondly the moral greatness of Clay, the grandeur of Daniel Webster, the intellectual superiority of Calhoun, and shook his head. Why must we always reject the best?

What do I think now?

While I may have thought him a hypocrite too, I can also appreciate that the issues of slavery at the time were not uncomplicated! People in the United States had already been living this way for a couple of centuries. I have no doubt that the slaves wanted to be free, but they didn’t necessarily want to be shipped off to Africa. (Not that anyone was asking them.)

I can’t help but wonder: What would have happened if Clay had lived another 10 years? (He died in 1852, nine years before the Civil War started.) I’m apparently not the only one who wonders about that. Robert V. Remini, historian of the U.S. House of Representatives and author of Henry Clay: Statesman for the Union was quoted in a Smithsonian magazine article as saying, “If Clay had been alive in 1860, there would have been no civil war.” (But what would his next compromise have proposed as a solution for emancipation that both the North and the South would have eventually agreed to? I really can’t even guess.)

Wonder what my ancestors thought?

NOTE: Henry Clay is a relative, but not an ancestor. (I am not descended from him.)

You may remember my blog post Black Lives Matter in Genealogy Too. The subject of that post, Lydia Dent Ferrel Mangum (a widowed slaveholder of uncertain racial makeup), had a granddaughter, Victoria C. Byrd (my 2X great-grandmother), who married into the Clay family. I wonder what my southern Mangum, Cannady, Byrd, Ferrell, Dent and Clay ancestors all had to say about their prominent relative, Henry, around their dinner tables in 1850? Not to mention my northern Quaker Thornton, Harris, Wilkins, and Henderson ancestors! (Thornton Family History Lost & Found).

What benefit have you derived from finding common ancestors?

Are you related to a historical figure? Are you sure? Would you like to find out?

What have you learned about history through your own genealogy research?

Please share with us in the comments below!

——————————————————————————————————

Copyright 2022 by Hazel Thornton, Organized for Life and Beyond

Author of What’s a Photo Without the Story? How to Create Your Family Legacy

Please contact me for reprint permission. (Direct links to this page are welcome!)

————————————————————————————-—————

Share this:

I find this fascinating, though I’m not sure I’m curious enough to pursue this type of research!

I think I might be related to a US senator from the early 20th century, but it’s possible I made the mistake of assuming a match I found was correct instead of investigating it further. I think this post might be a good starting point to figure that out!

It’s possible that you and your match both made a mistake. But it should be easy to follow your match’s breadcrumbs and find out! If the generations are really linked, and there is documentation of it, it shouldn’t take long to prove or disprove.

What an exciting story about Clay. Congratulations on your achievement.

As I studied and learned information about my ancestors for over 30+ years, I found that it is imperative that I dig deep into the facts. Both sides of my family use the same names resulting in a lot of confusion. They primarily would name their children, their parents’ names so the years were always an issue.

Exactly! Um, which Thomas Thornton? The one born in 1698, 1735, 1762, 1804, 1840, 1845, or 1860? But also, if you know that (or wonder if) a family followed traditional naming conventions for their children you can make a guess at the grandparents’ names and possibly find documentation that you were right. Or not. It’s just a clue. Glad you liked my story, Sabrina!

Well how cool is that? I think that’s pretty neat!!! I really didn’t know much about Henry Clay. I think we know only fragments about historical figures. This was interesting to read and learn a bit more about him.

I read an article recently saying that we have a “doppelganger”… aka, twin, and that we are probably related. Reading this gives me pause, and makes me realize that I can be related to just about anyone.

Oh, there’s tons more about Henry Clay than I could fit into a blog post! I’m glad you enjoyed it. And I saw that same doppleganger article. I think I have (or had) one here in Albuquerque. In addition to people saying I looked familiar when they met me (back when I was networking a lot for my business) there was one grocery clerk who insisted that I was a regular, when I really wasn’t. I even think I saw her once, but it was in the rear view mirror of my car and I learned nothing from the experience that would lead me to her. (I suppose I could have staked out the grocery store, but that could have taken forever and never panned out.)

This is fascinating stuff, Hazel. My husband likes to do the genealogy research and has found interesting relatives and ancestors along the way.

I agree with you – I think we ARE all related. It just takes time and patience to find out how.

I’m glad you think it’s fascinating, Diane! Sometimes I wonder if I’m the only one, lol. Yes, it can take a LOT of time, and a LOT of patience.

Hazel, this is like a class in history, the craft and science of genealogy, and the philosophy of statesmanship, all rolled into one. I’m fascinated, even though (as always) my eyes start to glaze over with charts of relatives and generations.

Thank you for sharing your compelling history with us!

I am also supposedly related to Henry Clay. I’ve been trying to find a DNA link to confirm it. I’m just not sure how to go about that. He is supposed to be my 4g grandfather. Please email me if you have suggestions. Thanks

Thanks for your comment, Christy! I’ve emailed you as requested!

I’m a clay too I’m pretty sure I’m related and have read a lot about Henry and his family!! Hey cuz

Hey! Nice to meet you!

I don’t know of I’m related but my dad is kevin john moore and I’m alden henry clay moore. so I thought that it could be significant? please email me if you have answers

aldenmoore531@gmail.com

Hi there — I don’t have any Moores in my tree, but I’ll keep a lookout for them!